By Colin Michel and Luke Billingham

In this piece, Colin Michel and Luke Billingham introduce their article on relational practice in adolescent safeguarding systems. To download as a pdf, click here.

Register here to attend the next webinar on Tuesday 15 April, 10:30-12:00 hosted in collaboration with Partnership for Young London.

In the first webinar, held in September, Colin and Luke explored the principles of the paper with youth practitioners from around London. For the third webinar in this series, Colin is delighted to introduce Victoria Ing, adolescent safeguarding practitioner and social worker, Southwark Council’s Adolescent Sure Start team.

Vic and the team are providing early support to young people in Southwark, via a network of community-based youth support hubs, and working closely with local community organisations to promote youth welfare and safety.

Vic recently worked on a project involving bike-building and BMX sessions with groups of young Londoners living on a Southwark estate that is affected by criminal exploitation and serious violence. This took place in parallel to the team’s pilot youth support hub opening on the estate. The bike project responded to community complaints about disruption and bike theft by young people, tackling the issue head-on, and in the process seeking to reduce risk, harm, and youth entry to the criminal justice system.

The project grew organically out of conversations between the council, residents, the police, education and community partners. It is a superb example of relational practice in action, with a focus on getting young Londoners into safe local spaces and building their agency, relationships, and wellbeing, by connecting them with a network of protective activities and adults.

At the webinar, Vic will share experiences and learning from this project, and then Vic and Colin will explore with participants the implications for relational practice in adolescent safeguarding.

There will be a further webinar taking place on Wednesday 14 May, 10.30-12.00.

A launch event for Adolescent Safeguarding in London (ASIL): Updated guidance for 2025. Guests TBC. Register here

Colin and Luke would like to express their gratitude to Dez Holmes, Jeanne King, Sunniva Minsaas, Ben Byrne, Betty Lynch and Alex Honnan-MacDonald, who thoughtfully reviewed an earlier version of this article, and provided helpful comments and encouragement.

Summary

- The term ‘relational practice’ does not have an agreed definition (Lamph et al 2023). It is used to refer to several types of relationship: professional relationships in direct work with young people; how young people relate to themselves, to their multi-faceted identities and lived experiences (Davis and Marsh 2022), and to people, places, and services; and the relations between professional roles, organisations, and sectors.

- There is professional uncertainty about what is involved in relational practice despite agreement among researchers that trusted relationships with young people form an essential foundation for effective adolescent safeguarding.

- The capacities for attunement and analysis are vital for adolescent safeguarding, whether practised in social work, youth work, youth justice, policing, or other professions in direct work with young people. These capacities enable practitioners to form and sustain trusted relationships and to nurture young people’s wellbeing and agency.

- There are several constraining forces that can prevent relational practice from flourishing in adolescent safeguarding systems. These include:

- Relational practice is demanding on those working with young people facing complex risks and harms. Practitioners can be expected to nurture and sustain these relationships and to understand a child’s multi-faceted identity and characteristics with minimal practical guidance, while working within inflexible, excessive and/or conflicting procedures, with large workloads, and under considerable pressure.

- Managers can find themselves expected to narrow practitioners’ attention to risk management in work with young people. This can operate at the expense of attentiveness to relationships and limit the potential to support positive change in young people’s lives.

- For strategic leaders collaborating in multi-agency systems, the aliveness of relational practice with young people can sometimes get lost from view.

- Practitioner development of knowledge, skills and confidence through reflective supervision and systems leadership can support relational practice to flourish.

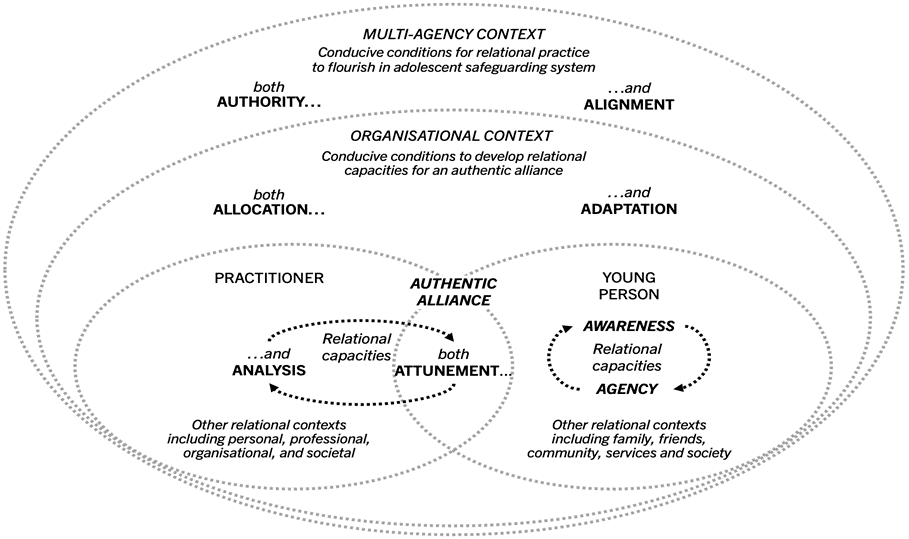

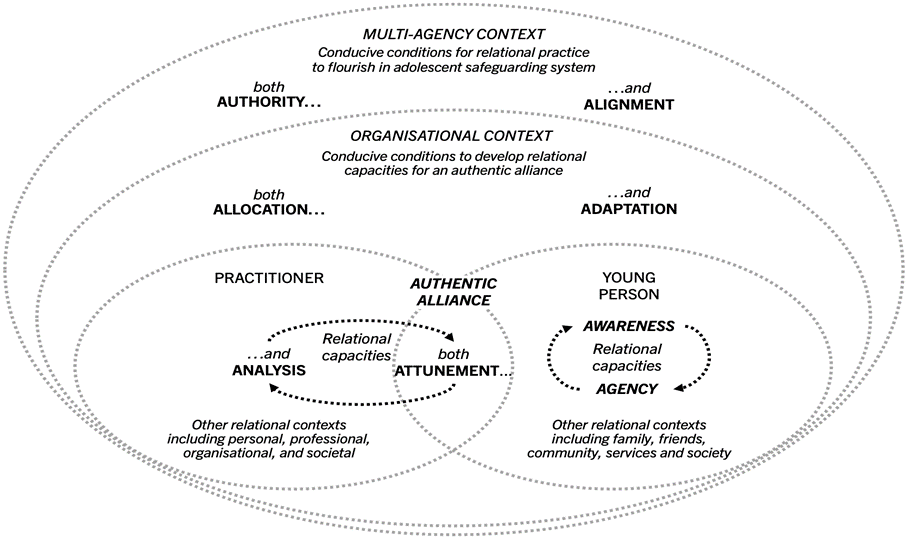

- We put forward a framework to show how conducive conditions for relational practice can be fostered. The framework aims to guide practitioners, managers and leaders, and to support exploration of constraints on and enablers for relational practice. Our aim is to strengthen the case for strategic leaders to create conducive conditions for relational practice to flourish in adolescent safeguarding systems.

Terms used in this article

The following definitions are included to explain how we use these terms in this article, when referring to adolescent safeguarding systems.

Agency: the capacity of a young person to develop awareness, make choices, take actions (Maynard and Stuart 2018), influence decisions, engage with the structures around them, and gain control over their lives (Jerome and Starkey 2022).

Awareness: ‘a catalytic process, sparking new thought or realisation, the outcomes of which are increased consciousness of ‘this is who I am’, ‘this is what I like and dislike’ and ‘this is what I am good at and not good at’’ (Maynard and Stuart 2018 p8).

Aliveness: a young person’s experience of being alive, as a thinking, feeling and acting human being. This includes their relation to themself, to people and places, and to risks and to harmful situations they are facing.

Attunement: the capacity for connectedness with a young person, and for responding flexibly to their emotional needs and desires (Pryce 2012). We propose that growing this capacity enables practitioners to heighten their empathy with – and comprehension of – a young person’s individual experiences.

Analysis: the capacity to step back and think about the young person’s strengths, needs, relationships and situations from several angles. To grow this capacity, practitioners think through changes needed to shift a young person’s situation in a positive direction.

Allocation: the management capacity to give authority to a practitioner to spend time working with young people with the aim of improving their outcomes. When using this capacity, managers consider the complexity of working with the young person, the practitioner’s capacity, and the time needed for supervision and continuing professional development (LGA 2024)

Adaptation: the professional capacity to adjust practice in response to emerging needs of young people (Khoury, Boisvert-Viens & Goyette 2023) with the aim of sustaining working relationships with young people. This includes management capacity to give authority to practitioners to use creativity and respond flexibly to the emerging needs of young people.

Authority: the power given to practitioners in a professional role through legislation, agency duties and organisational policies and procedures. This includes leadership and management powers to place duties on practitioners to take decisions and actions in their practice.

Alignment: strategic leadership capacity to collaborate across multi-agency systems to create conducive conditions for relational practice to flourish.

Practitioner: someone who carries out direct work with young people, whether in paid work or as a volunteer.

Professional: someone who is paid to take up a skilled role with or on behalf of young people, including those in direct practice, first-line management, senior management or strategic leadership.

Relational practice: we do not propose one ‘catch-all’ definition for relational practice, but we believe it involves a commitment to collaboration that sustains trusted professional relationships with children, young people and families, and between professionals. We think relational practice gives priority to relationships as a foundation for effective practice in general.

A framework for creating conducive conditions in multi-agency contexts

Imagine that…

…you’re a youth practitioner for a local charity supporting young people at risk from serious harm. You’ve been working with Saif since he was 13, when he was permanently excluded from school after he injured another student with a knife. The youth court sentenced Saif to nine months in a young offender institution.

Saif used to say you were the only adult he trusted.

Saif’s now 16, and since his release from the institution, it feels like you’ve stopped getting through to him. He skips your meetings and does not turn up to his training placement. You worry speaking to the police could further damage his trust in you.

In supervision with your manager, you describe feeling overwhelmed, and fearful Saif might be harmed, or do harm to others. You reflect upon these feelings but remain uncertain how to create safety with Saif in spaces beyond your one-to-one relationship.

…you’re a social work team manager for the local authority. You run weekly meetings where practitioners from different services come together to discuss ways to safeguard young people from serious violence and exploitation.

You feel pressure to allocate widely the limited local resources to support young people. You are angry about public callousness toward young people’s welfare.

You report a sharp increase in demand over six months, and senior managers at the multi-agency partnership meeting consider available resources for direct practice with young people at risk of harm from violence and exploitation.

…you’re a superintendent for the local policing area. You chair quarterly meetings alongside fellow strategic leaders from social work, healthcare, community safety, education, and housing services, where your shared aim is safeguarding children from harm by analysing themes in data and intelligence.

You are worried that local practitioners avoid sharing information that could help the police to prosecute young perpetrators of violence. Weapons injuries and child criminal exploitation are rising, and the police must act to disrupt these harms.

You raise your concerns at the meeting and explore your position with the group. They propose deeper analysis of violent incidents and unsafe spaces. The group commissions participatory work with young people and practitioners to seek more opportunities for creating safety with peer groups. They agree to reallocate limited existing resources to support more young people at risk of harms.

1. Relational practice for adolescent safeguarding systems

About the scenario

The scenario that opens this article evokes some emotions and dilemmas routinely experienced by practitioners, managers, and leaders, who are involved in multi-agency collaborations for safeguarding young people. We describe how each of the professionals in this scenario might feel, and what might happen if conducive conditions were in place to support relational practice. The scenario draws on our own experiences and conversations in our respective roles as a consultant to local multi-agency safeguarding partnerships (Colin) and as a youth worker and researcher (Luke).

The scenario illustrates what we mean by relational practice for adolescent safeguarding, referring to several different but connected ways of being in both “relationship with” and “relation to” others (Long 2016). The definition includes professional relationships with young people, with attention to multifaceted identities, social positions, and how these may have affected young people (Davis and Marsh 2022); how young people relate to themselves, and the relationships within their lives, such as their friendships, kinship, and community relationships; and the relationships between professional roles, services, organisations, sectors, and disciplines.

The scenario also helps to demonstrate what we mean by adolescent safeguarding systems in England (Firmin and Knowles, 2022). We define an adolescent safeguarding system as a purposeful multi-agency collaboration, undertaken at levels of direct practice, operational management, and strategic leadership, and in partnership with young people, families and communities. The uniting aim of the system is to create safety with young people exposed to risks and harms, prevent further harm, and nurture wellbeing and agency. We recognise risks and harms arising both within and outside of family. We suggest this definition has four important implications for relational practice.

- Firstly, it centres young people’s wellbeing and agency as the goals of adolescent safeguarding without placing on young people the responsibility for reducing harm.

- Secondly, it recognises the vital influence of non-professional relationships in the lives of young people within adolescent safeguarding systems.

- Thirdly, effectiveness of adolescent safeguarding extends beyond the scope of any one organisation or sector, emphasising quality of collaboration within partnerships.

- Lastly, the term system underlines the interrelatedness of all the different parts of the adolescent safeguarding system to one another. The term indicates the complex and changing nature of adolescent safeguarding, which requires curiosity and flexibility from leaders, managers and practitioners, rather than rigid forms of management.

Why relational practice? Which relational practice?

There is strong evidence that trusted relationships between practitioners and young people facing risks and harms form a crucial foundation for creating safety (Commission on Young Lives 2022; Firmin et al, 2024; Holmes, 2022; Lamph et al 2023; Lefevre et al, 2019; Lewing et al 2018; Lloyd et al 2023).

Hill and Warrington have argued convincingly that youth participation and empowerment are fundamental to high quality relational practice and to creating meaningful safety in young people’s lives (2022). In this spirit, young people have made clear trusted relationships are paramount for safeguarding them from risks and harm. For example, based on an extensive engagement exercise with young people, Millar, Walker, and Whittington report that young people want services which:

adopt a relational approach, underpinned by trust and relatability, and which strive for collaboration and power-sharing between young people and adults, rather than surveillance and monitoring of young people’s behaviour (in Firmin and Lloyd 2023, p119).

Despite this consensus, we have found widespread professional uncertainty and anxiety about what is involved – and not involved – in doing relational practice. This uncertainty is not helped by the lack of a coherent, comprehensive model for relational practice (Lamph et al 2023) despite the term being widely researched, described and applied in the relevant service sectors, including social work (Ruch 2020), youth justice (HMIP 2023), youth work (Hennell 2022), education (Dunnett and Jones 2020), and general practice (RCGP 2022), among others.

Variations in the descriptions and applications of relational practice within and between these service sectors likely contributes to the professional uncertainty and anxiety. There is also a range of models for practice commonly used in adolescent safeguarding systems, which overlap with relational practice, such as in the connections between strength-based and relationship-based approaches (Tackling Child Exploitation 2023), in trauma-informed practice that responds to extra-familial risks and harms (Hickle 2019) in restorative practice in education (Finnis 2021). Relational practice for adolescent safeguarding also asks practitioners to apply an intersectional and systemic perspective to consider young person’s lived experience of race, gender, class, faith, sexuality, ability/disability and other characteristics (Davis and Marsh 2020, 2022).

In response to the research consensus and to professional uncertainty and anxiety about relational practice, we next describe two relational capacities we believe are essential in the doing of relational practice: attunement and analysis.

The capacity for attunement

Attunement is a capacity for connectedness while being with a young person. Using this capacity enables a practitioner to heighten their empathy with – and comprehension of – a young person’s experiences (Gilkerson and Pryce 2021, Stern 1985). This capacity requires the practitioner to develop deep attentiveness in the here-and-now (Mann 2020) to tune in with the young person’s emotional state. Attunement enhances the practitioner’s sensitivity to emotional feedback loops (Hollenstein 2015) between the young person’s feelings, thoughts, and reflections (Gilkerson and Pryce 2021). This can then sharpen the practitioner’s capacity to comprehend the aliveness of the young person, thoroughly engaging with their present experience as a thinking, feeling and acting human being. This includes their relation to themselves, to their multi-faceted identities and lived experiences (Davis and Marsh 2022), to the people and places in their lives, and to risks and harmful situations they are facing.

The capacity for analysis

When working with young people who experience complex risks and harms, professionals often encounter safeguarding dilemmas (Beckett and Lloyd 2022). Analysis is the capacity to step back, to think about the young person, their relationships, identities, and situations from multiple angles, applying a variety of methods to think through the changes needed to shift their situation in a positive direction, especially in relation to risks and harms. This may include, for instance, case formulation, and intersectional and systemic thinking (Davis and Marsh 2020) while working with young people, and in dialogue professionals in multi-agency discussions.

Analysis is primarily a reflective capacity, and most often happens not when being with the young person, but before or afterwards, while reflecting on what has come up with the young person about their situation and relationships, often in collaboration with managers, supervisors or peers. Practitioners analyse connections between risks and harms, including between those inside and outside the home, or between interpersonal and structural harms (Wroe and Pearce 2022; Billingham and Irwin-Rogers 2022). Of course, in some cases, practitioners must think and reflect in action (Schön 1992), which involves in-the-moment analysis as a situation of risk in the life of the young person develops. Ideally, and whenever possible, practitioners create opportunities for analysis to be undertaken with the participation of the young person, alongside them. This requires practicing attunement as described above to strengthen participation (Hill and Warrington 2022), combining emotional engagement with analytical exploration.

Nurturing young people’s wellbeing and agency as the core aim of adolescent safeguarding systems

The aim of adolescent safeguarding is often defined in narrow terms, as the prevention of harm to young people, perhaps because these terms are a primary focus for children’s social care (Maynard and Stuart 2018). We propose a broader aim for adolescent safeguarding: multi-agency collaboration to create safety and wellbeing with young people. Maynard and Stuart define wellbeing as ‘feeling good and functioning well’, and link wellbeing to ‘equality, equity and the ability to use capabilities to function freely in the world’ (2018 p169). This idea that wellbeing is both ‘feeling good’ and ‘functioning well’ aligns with a definition of human flourishing as both fulfilling needs and thinking and feeling positively about life (Billingham and Irwin-Rogers 2022).

By using relational capacities for attunement and analysis, practitioners contribute to adolescent safeguarding by supporting young people to develop both wellbeing and agency. Young people’s agency can be understood as developing awareness, making choices, and taking actions (Maynard and Stuart 2018), and influencing decisions, engaging with the structures around them, and having control over their lives (Jerome and Starkey 2022). By enabling agency, practitioners work to enhance young people’s belief in their own abilities to stay safe, and promote their own wellbeing, while also working to create safety in spaces where harm is happening.

While we place the development of a young person’s agency at the heart of our understanding of relational practice, we do so with caution. Owens and Lloyd have highlighted the problem of safeguarding responses that intend to prevent, but that place too much responsibility on young people to change their own behaviour, and not enough on professionals to create safety in places and relationships where harm is happening (2023). This problem leads not only to young people being left in harmful situations without protection from abuse, but also contributes to the skewed perception that young people who have been harmed by different forms of violence and exploitation are the source of those harms, often categorized as ‘youth violence’ (Billingham and Irwin-Rogers 2022).

It is crucial for practitioners to understand relational practice as an opportunity for collaboration that creates safety with young people by supporting them to build their own wellbeing and agency, without placing primary responsibility on them for the alleviation of risk and harm (Beckett and Lloyd 2022), and in combination with activity aimed at addressing the contexts of their exposure to risk and harm. To fully address the contexts of harm, professionals in adolescent safeguarding systems must also be supported to build awareness of how racism, biases and wider forms of discrimination can prevent professionals from providing a safeguarding response (Davis and Marsh 2022) that is focused on nurturing young people’s wellbeing and agency.

As with many other dimensions of relational practice we discuss below, what Holmes (2022 p19) describes as a ‘both/and’ mindset is helpful: we can both support young people’s agency to navigate risks in their lives and recognise that we as safeguarding professionals have a responsibility to strengthen safety in their social environment. We must both work to understand multi-faceted aspects of a young person’s identity (Davis and Marsh 2022) including how structural discrimination can diminish a young person’s subjective wellbeing (Billingham and Irwin-Rogers 2022) and recognise that there is a need for nurturing safety, wellbeing and agency, in every young person’s life.

2. Constraining forces on relational practice in adolescent safeguarding systems

In this section, we outline the various factors and forces which can make the achievement of relational practice more difficult, at the levels of direct work with young people, management and supervision, multi-agency systems, and leadership.

Doing relational practice with young people

Enacting attunement and analysis to create safety with young people and to support them to develop wellbeing and agency makes practice a complex experience. Skillful development and creative application of these capacities requires balance and resourcefulness (Trevithick 2012) especially in relationships with young people who are facing complex risks and harms. Using the capacity for attunement is emotionally demanding, more so when sustaining relationships with young people who are holding painful memories of past experiences and are distressed about situations in the present.

The ideal practitioner will have highly developed capacities for attunement and analysis and will apply a well-rounded balance of the two. It is challenging for any practitioner to balance these capacities in tandem, and to learn when and how to apply them with ease. There will be practitioners who feel more confident and skilled in the use of one capacity compared with the other. Developing both capacities – and fine- tuning the balance between them in different situations – can be understood as a priority for effective practice. There is no perfect ratio to be found between attunement and analysis, and finding the balance is a dynamic process, depending on the changing situation of the young person. This balance can involve feeling pressure, in the moment, to connect with the young person’s interests, identity and circumstances, to follow the flow of relatedness with them, while also using emotional reasoning (Trevithick 2012), and remaining alert to potential risks and harms.

The practice of modulating between attunement and analysis is demanding, emotionally, intellectually, and creatively. It involves an oscillation between forms of attentiveness that are in some ways at odds with one another. To switch between capacities involves emotional engagement then disengagement, flexing a relational muscle between feeling and thinking. Practitioners may need to slide between modes very rapidly, sometimes while in the presence of the young person. The pursuit of effective practice can therefore be exhausting, especially with a young person who is experiencing considerable trauma.

Practitioners use attunement to sustain empathy and avoid overt reactions in the presence of often very negative emotions, including when a young person actively seeks to provoke the practitioner. Complex feelings toward the young person, their circumstances and the harms they face may arise when switching between capacities. This can mean challenging the young person’s actions and beliefs where these are leading to an increase in the risk of harm to themself or to others, without breaking trust. The practitioner may have to soothe themself as they rip attention from emotional engagement with the young person to carrying out analysis. For this reason, relational practice for adolescent safeguarding can be highly demanding on all aspects of practitioner wellbeing and self-efficacy.

Professional learning and development for relational practice

The capacity for attunement in the here-and-now, can be understood as an experience of relational depth, a quality of the therapeutic relationship (Di Malta et al, 2024). Research suggests that relational depth supports wellbeing beyond psychotherapy settings and may be facilitated via professional development (Di Malta et al, 2024). Practitioner development of the capacity for attunement is an ongoing process that continues to enhance relational depth, and to complement vital practice tools, such as formulation with the young person about the sense they make of their situation.

Attunement is difficult to learn in the classroom, and some practitioners may find they learn about and develop this capacity more easily than others. We think attunement can be affected significantly by the social proximity of the practitioner to the young person.

This means practitioners may find attunement with some young people comes more easily or more swiftly than with others. Young people participating in research emphasise that relatability is a condition for developing relationships with practitioners (Millar et al 2023).

Davis and Marsh (2022) drawing on Crenshaw (1991) have emphasised that practitioners must apply an intersectional lens to understand how each individual young person’s biological and social ‘characteristics influence their everyday experiences, including the response they receive from professionals and services’ (p119). This suggests that developing the capacity for attunement with young people, and responding to the importance of relatability, must always mean examining our biases and ‘our perceptions of them, recognizing that this also shapes our response’ (p126).

A further challenge with the capacity for attunement is that the better it is carried out, the less it can appear as effortful work. Gotby has argued the results of emotional work are not always apparent as work per se, because they appear as part of the personality of the worker (2023, xv). In this sense, attunement is challenging, as it is an emotional labour not recognised as requiring high skill levels, or is deemed to be solely an expression of a practitioner’s innate qualities. This can have several demeaning effects, including lack of adequate pay and recognition and a patronising exoticisation of practitioners as ‘youth whisperers.’ Comparable to the all-too-often belittling experience of teaching assistants and learning mentors in some education settings – tasked with ‘doing relationship work’ – this condescension is often both classed and racialised. The notion of ‘innate’ attunement skill can imply that some practitioners are by nature inherently better at this capacity than others, which can diminish the efforts of practitioners who work hard to build relational capacities and can dissuade other practitioners from seeking to nurture them. Again, this is best approached with a ‘both/and’ mindset. It is of course true that the capacity for attunement is always partly grounded in tacit knowledge, is deeply embodied, and is affected by a practitioner’s personality, making it difficult to grasp in the abstract. But it is also a capacity which can be honed through professional and personal experience, reflection, and supervision.

Practitioners can participate in learning opportunities to strengthen their capacity for analysis. At best, practitioners will be supported to feel flexible and resourceful, able to deploy a repertoire of analytical tools to help them understand the situation facing the young person, and to plan support. Practitioners can use language and models for analysis which resonate with and make sense to those they are supporting, and they can collaborate with young people to carry out safety mapping that actively involves young people in analysis of risk in places, spaces and relationships. Though a more intellectual and less deeply personal capacity than attunement, some practitioners feel more comfortable and confident than others to use analysis. Analysis can be explored, modelled, and supported through informal reflective activities with peers and senior practitioners, and through formal development in management, supervision and training.

At present, it often appears that practitioners working directly with young people, across the disciplines of social work, youth work, healthcare, policing, and housing services, to name a handful, are too often expected to just do relational practice. Many practitioners sustain relationships for adolescent safeguarding with minimum guidance and training, despite challenging conditions such as heavy caseloads, high stress levels, vicarious trauma, and demanding record-keeping and monitoring.

Managing and modelling relational practice

Practitioners working directly with young people are charged with the responsibility for relational practice that deepens their insight into harsh realities in young people’s lives and face burgeoning safeguarding dilemmas. Acting on this responsibility has a significant emotional impact (Scott and Botcherby 2017). There are often too few spaces for first-line managers to provide emotional support for practitioners to process what they experience in direct work with young people who face complex risks and harms, and to support the development of their capacities for attunement and analysis.

There are likewise too few spaces for first-line managers to enter dialogue about relational practice with each other, as managers. There is too often a lack of space and time for line managers at all different levels of adolescent safeguarding systems – from team managers to director-level leaders – to participate in collaborative learning opportunities about the social and economic realities facing young people, their identities, peer groups, families, and communities, not least the impact of structural inequalities and disparities. There are similarly too few spaces for senior managers to reflect with each other on adolescent safeguarding research, policy and practice. In a recent interview Professor Eileen Munro has noted that senior managers can become too detached from practice, and “forget quite how messy and chaotic the reality of it is” (Koutsounia 2024).

First-line managers are typically expected to centre practitioners’ attention on the assessment and management of risks in young people’s lives. This form of risk-based managerialism (Trevithick 2014) can result in preventing the development of deep attentiveness and can limit the potential of those relationships from being a source for positive change in young people’s lives. This is made more challenging when conditions needed for enduring relationships are not established, and there are not enough resources to sustain relational practice (Firmin, Lefevre, Huegler and Peace 2023).

Consequently, a gap can open between practitioners who are prioritising the welfare of young people whom they know well, and managers who are often expected to manage limited resources and responses to the work of reducing high risks and harms. This practical gap can, in turn, produce an emotional gap, and sometimes interpersonal tensions, not only between practitioner and manager, but also between the experiences of managers, and those of young people and families. Researchers have argued this kind of gap ‘may lead to a defended system, where control and stability are prioritised over relationships with young people’ (Lloyd et al 2023, p13).

Relational practice within multi-agency systems

A different type of gap can open between managers from different sectors who have varied levels of exposure to practice models. Owens and Lloyd describe challenges of shifting mindsets within adolescent safeguarding systems from a behaviour-based approach to one that focuses on relationships, collaboration between professionals, and creating safety with young people (2023). Social workers are expected to lead collaboration for statutory safeguarding (Owens and Lloyd 2023). However, partnerships between sectors do not often ‘[acknowledge] differences in conceptual and ideological frameworks’ (p17) and managers from social work, policing, education, youth justice, youth services, healthcare, and housing, among others, are not always supported to collaborate effectively within a shared framework of values and principles. This can contribute to uncertainty and anxiety about relational practice described above.

Further, skilled non-statutory practitioners, such as those working with young people in education and community settings, are not always offered opportunities to contribute in person to multi-agency meetings for the management of safeguarding responses. They receive requests for written information, but experience side-lining from dialogue, assessment, and formulation, and at worst condescension from statutory partners.

In their recent study about the role of relational practice within adolescent safeguarding systems, Firmin et al (2024) make a useful distinction between young people who are ‘known-to-services’ and those who are ‘known-by-professionals’ who support them. This research reveals that responses focusing on the behaviour and choices of young people can reinforce ‘emotional, cultural and emotional distance between professionals and those in need of support’ (p7). In these situations, the

needs and experiences of young people and families were less relevant, and they did not appear to shape the plans put in place to support them [and] when young people are ‘known-to-services’, rather than ‘known-by-professionals’, plans developed to support them may be designed without much knowledge of, or conversation with, the young person (Ibid)

A further barrier arises from this problem identified by Firmin et al: professionals reviewing the cases of young people and families who have been ‘known-to-services’ (as opposed to known-by-professionals) for many years can conclude that these young people and families have received support over several years with ‘no effect’. This can reinforce stigma and compound discrimination, labelling young people and families as those who ‘cannot be helped’.

Leading relational practice

A key issue constraining the development of relational practice for adolescent safeguarding systems is that ‘the practice or community conditions required for such relationships to flourish are yet to be firmly established’ (Firmin et al 2022, p42). In the experience of the first author (Colin), leaders collaborating in multi-agency safeguarding systems are often committed to the principles of relational practice, and demonstrate this commitment through strategy, policy and improvement plans. It can, however, be challenging to consistently demonstrate and embody this commitment at an organisational level. Firmin et al (2022) have noted ‘references to [relational] principles proliferated in studies examining practice interventions but [are] much less obvious in organisational or whole system approaches to addressing [risks and harms outside of the home]’ (p39) As a consequence, for strategic leaders, the aliveness of relational practice with young people may not be visible or tangible in leadership meetings.

One observation gained from consulting with leaders in several multi-agency partnerships in England, is the prevalence of dialogue between leaders about meetings. A common action is to rearticulate the purpose, composition, frequency, scope, participation, and so on, of such adolescent safeguarding meetings. Across England, overarching outcomes such as human flourishing, described above, are listed in these documents. In many cases, terms of reference, strategies and improvement plans include young people’s rights to enjoyment, wellbeing, safety, learning, participation, and so on, and these rights are presented and discussed in leadership spaces. However, the words applied in these documents can sometimes appear tokenistic: strategic leadership meetings may refer to the principle of relational practice, but do not always make present the doing of relational practice.

In this way, multi-agency leadership groups can be constrained from thinking meaningfully about relational practice and conducive conditions needed for it to flourish. Strategic partnerships between leaders from different sectors and disciplines ostensibly focus on driving effectiveness in multi-agency adolescent safeguarding systems but may end up limiting the scope to performance data, information sharing, and the availability of resources. Strategic partnership groups can struggle to achieve momentum in applying learning, and to make relational practice present as the primary purpose of multi-agency adolescent safeguarding systems.

In summary, there are several challenges that constrain practitioners, managers, and leaders from developing their capacities for relational practice. Enduring relationships between professionals, and crucially, between practitioners working directly with young people are fundamental resources for effective adolescent safeguarding systems. When used effectively in tandem, the capacities of attunement and analysis can support dynamic working alliances between practitioners and young people, enriching young people’s wellbeing and agency. More work is needed, then, to describe the creation of conducive conditions that would benefit young people, practitioners, managers, and leaders alike, and enable high quality relational practice to resonate through multi- agency safeguarding systems. We turn to this topic in our third and final section.

3. Creating conducive conditions for relational practice in adolescent safeguarding systems

9xAs: conducive conditions for relational practice in adolescent safeguarding systems

We offer this framework to explore how conducive conditions for relational practice might be described, fostered, and bolstered at each level of adolescent safeguarding systems. We emphasise that this framework makes no prescriptions for policy, protocol, or practice. We have brought its elements together with the aim of supporting professionals to think together beyond the bounds of specific professional services, sectors, and disciplines.

The framework aims to offer guidance to professionals working in adolescent safeguarding systems, to support exploration of the benefits of relational practice, and to strengthen the case for strategic leaders to enhance conducive conditions for its flourishing. The framework invites professionals, at the levels of direct practice, management, and leadership to take up what Holmes has called a ‘both/and’ mindset (2022 p19), which might mean attending both to experiences, identities, relationships and harmful circumstances facing a young person, and focusing on their agency and wellbeing.

The framework invites a similar attention from managers and leaders, asking them to use this mindset for thinking about change in adolescent safeguarding systems to create conducive conditions for relational practice. For instance, first-line managers may need to consider both the conditions needed for practitioners to develop attunement and their analysis of potential harms, and the fine-tuning of the balance between these two. To do this, first-line managers would apply attunement and analysis with practitioners, modelling relational practice, in parallel with the application of these capacities by practitioners with young people.

Organisational context: both allocation and adaptation

In the first part of this paper, we put forward two key capacities for practitioners – attunement and analysis – which we think are the key conditions for the development of an authentic alliance with young people. When it comes to management support for this authentic alliance, we propose that the first key condition is the allocation of dedicated space and time for professional development, particularly to develop and apply the capacities of attunement and analysis. This gives authority to a practitioner to spend time working with young people, and when using this capacity, managers consider the complexity of working with the young person, the practitioner’s capacity, and the time needed for supervision and professional development (LGA 2024). Relational capacities for adolescent safeguarding cannot depend simply on communication skills training but is best supported through a combination of practice, reflection-on-practice, supervision, and peer discussion.

Managers would also create the second key conducive condition: the adaptation of service delivery to learning emerging from practice with young people. This would mean recognising the need for flexibility in the use of practice models and tools, so that practitioners can develop and apply attunement for relational depth (Di Malta et al, 2024). This will allow first-line managers to make visible in the wider system new learning emerging from practice, making this present in reporting to senior managers and strategic leaders within adolescent safeguarding systems. This entails a recognition of professional knowledge and learning gained by practitioners through experiences of relational practice, and a willingness to facilitate ‘bottom-up’ changes to procedures, protocols, and strategies.

Professional development activities would include reflective practice, which can be supported through guidance, observation, debriefings, one-to-one and group supervision, to name a few options. Allocation and adaptation would create conditions to focus on developing attunement and analysis. Professional development would aim to sharpen the focus of both capacities upon the aliveness of the young person’s experience. This aliveness includes how the young person’s thinks and feels about their own wellbeing and agency, about their relation to themself, their multifaceted identity and social position, the relationships in their life, about the social roles they play, and about the situations of risk and harm they face.

Reflective practice helps professionals understand emotional experiences in direct work. The concepts of holding environment (Winnicott 1960) and containment (Bion 1962) explain how parents create situations where children learn to cope with difficult emotions, and in parallel, professionals provide containment for young people and families, and supervisors provide containment for practitioners. Williams, Ruch and Jennings stress the ‘central importance of containment in the face of the anxiety-ridden professional contexts [and] the need for participants to be permitted to be professionally vulnerable, in order to maintain a position of professional curiosity’ (2022, p19). As such, first-line managers who tune into the emotional experience of practitioners in their direct work with young people can be seen as a parallel form of attunement with practitioners, and their experiences with young people. Or, put another way, ‘supporting supervisors to support practitioners, to support parents, so they can manage the anxiety they experience in order to enable them to provide care for their children’ (Williams et al 2022, p19). Allocation and adaption serve to create conditions that prevent practitioners from becoming disillusioned and burned out and approaching work in an emotionally disengaged manner. In turn, senior managers create conditions that aim to prevent disillusionment, burn out and emotional disengagement in those who are responsible for managing direct practice.

Multi-agency context: both authority and alignment

We propose that in multi-agency collaboration, strategic leaders need to create conditions for relational practice by giving authority to senior managers, first-line managers and practitioners to prioritise nurturing young people’s wellbeing and agency via the development of relational practice. This would make relational practice present as the core function of adolescent safeguarding systems.

David Armstrong (2005) has proposed that a ‘neglected function of leadership’ is making present, which he describes as an ‘act of discernment, of bringing into view and articulating what is often tacit’ (p133). Armstrong emphasises that to discern the most valuable ‘goods’ within an organisation, leaders should reflect on examples of excellence in the skills essential to practice (p130). We propose that one crucial function of leadership in adolescent safeguarding systems is to reflect on capacities of attunement and analysis at the heart of relational practice as the valuable ‘goods’ of the system, and to recognise ‘it is the practice that breathes life into the organisation’ (p131). Armstrong argues the leadership of an organisation ‘secures and selects resources’ so that ‘goods and conceptions’ internal to practice can be ‘realised and extended’ (p132).

This emphasis on authority for securing resources so that the benefits of practice can be realised is echoed by Doherty and St Croix in the context of supporting youth work:

conditions for high quality youth work centre on […] long-term investment, support for professional training and education, the valuing of staff through decent contracts, and halting the sale of buildings and the closure of popular grassroots facilities […] rebuilding of an adequate and proportional youth work sector that is able to have an everyday value and a remarkable impact on young people’s lives. (Doherty and de St Croix 2019)

This would require leaders to give authority to senior managers to reflect on and use critical thinking for the alignment of policy and practice functions within adolescent safeguarding systems. This alignment would support critical examination of professional development approaches that bolster strong professional identity and practice for multi-agency adolescent safeguarding (Williams et al 2022)

Writing about working with leaders in adolescent safeguarding systems, Byrne has observed that the emotional experience of effectiveness is dependent on relationships:

I’m sure many people will recognise the feeling when strategic partnerships move into their most productive phases; something clicks. What is increasingly evident is that that ‘something’ isn’t the result of fairy dust. It comes from having created the conditions, having invested in your partners and in shared development activity, and through each of us leading with care to achieve a common goal. Once you have made that investment as a partnership, and brought together the necessary ingredients, you just need to trust the process. (2021 italics added)

This summarises the work that leaders must do to create authority and alignment in adolescent safeguarding systems for high quality relational practice.

Conclusion

In this paper, we assert the importance of re-balancing the responsibilities for relational practice in adolescent safeguarding systems. Research and policy have widely reported that trusted relationships are one of the crucial conditions for reducing risks and harms in the lives of young people (Commission on Young Lives 2022; Firmin et al, 2023; Holmes, 2022; Lamph et al 2023; Lefevre et al, 2019; Lewing et al 2018; Lloyd et al 2023). Currently, we would suggest, there are two major factors often preventing these relationships from maximally flourishing: (1) there remains widespread uncertainty and anxiety about the doing of relational practice, and relatedly (2) there is too often an expectation that practitioners ‘just do’ relational practice. We argue that everyone within adolescent safeguarding systems should be more attentive to both the value and the complexities of relational practice and should work together to create conducive conditions for it to flourish throughout the system.

We anchor the development of young people’s wellbeing and agency as the primary purpose of relational practice for adolescent safeguarding. This puts the focus of adolescent safeguarding policy and practice on young people’s rights. We argue that supporting practitioners to develop the knowledge, skills, and confidence in their capacities for attunement and analysis are fundamental to the success of relational practice in adolescent safeguarding systems.

The effectiveness of adolescent safeguarding systems extends beyond the scope of any one service, organisation, or professional sector, thus entailing the crucial importance of effective relationships and collaboration within and between multi-agency and multi-disciplinary partnerships. Therefore, we would argue that adolescent safeguarding at its best is always relational and is best supported when relational approaches are adopted at every level of the local system. We propose that creating space and time for the development of capacities of attunement, analysis, and reflection, with attention to systemic and intersectional perspectives, at the levels of direct practice, management and leadership, can contribute substantially to creating conducive conditions for relational practice to flourish.

At the levels of operational management and multi-agency strategic leadership, commitment is urgently needed for the development of relational practitioners who can grow their capacities for attunement and analysis. This commitment means that managers need to be able to allocate resources, and support practitioners to be agile, adapting their responses to young people. We propose this would enhance the development of relational depth, supported by space and time for reflective practice, professional development, and effective leadership. In turn, this approach would make relational practice present as the core function of adolescent safeguarding systems, in service of nurturing young people’s wellbeing and agency.

Relationships are what we all live for. Within safeguarding systems, the right relationships – between professionals and young people, as well as among professionals – can be what keeps a young person alive. But no relationship occurs in a vacuum: every relationship needs conducive conditions for it to thrive.

References

Armstrong, D (2005) Organization in the Mind: Psychoanalysis, Group Relations, and Organizational Consultancy. London: Karnac

Beckett, H, Lloyd, J (2022) ‘Growing Pains: Developing Safeguarding Responses to Adolescent Harm’ in Holmes, D Ed. (2022) Safeguarding Young People: Risk, Rights, Resilience and Relationships. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Billingham, L & Irwin Rogers, K (2022) Against Youth Violence: A Social Harm Perspective Bristol: BUP

Bion, W. (1962). Learning from experience. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

Byrne, B (2021) ‘‘It’s not them, it’s us’: the making of a child exploitation strategy’ Tackling Child Exploitation Programme

Commission on Young Lives (2022) ‘Hidden in Plain Slight: final report’

Di Malta, Gina; Bond, Julian; Raymond-Barker, Brett; Moller, Naomi and Cooper, Mick (2024). The Impact of Relational Depth on Subjective Well-being in Close Relationships in the Community. Journal of Humanistic Psychology.

Doherty, L. M. & de St Croix, T (2019) ‘The everyday and the remarkable: Valuing and evaluating youth work’ In: Youth and Policy. 18 Nov 2019,

Dunnett, C & Jones, M (2020) Guidance for Developing Relational Practice and Policy. Devon County Council.

Finnis, M (2021) Restorative Practice: building relationships, improving behaviour and creating stronger communities Padstow: Independent Thinking Press

Firmin, C., Langhoff, K., Eyal-Lubling, R., Ana Maglajlic, R., & Lefevre, M. (2024). ‘Known to services’ or ‘Known by professionals’: Relationality at the core of trauma-informed responses to extra-familial harm. Children and Youth Services Review, 160, Article 107595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2024.107595

Firmin, C. & Knowles R. (2022) ‘Has the Purpose Outgrown the Design?’ in Holmes, D Ed. Safeguarding Young People. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Firmin, C. Lefever, M. Huegler, N. Peace, D (2022) Safeguarding Young People Beyond the Family Home: Responding to Extra-Familial Risks and Harms Bristol: Policy Press

Firmin, C. & Lloyd, J. (2023) Contextual Safeguarding: The Next Chapter. Policy Press.

Gilkerson, L & Pryce, J (2021) The mentoring FAN: a conceptual model of attunement for youth development settings, Journal of Social Work Practice, 35:3, 315-330,

Gotby, A (2023) They Call It Love: The Emotional Politics of Life. London: Verso

Hennell, K (2022) Article: A Relationship Framework for Youth Work Practice. Youth & Policy, 11 October 2022

Hickle, K. (2019) ‘Understanding trauma and its relevance to child sexual exploitation’

Hill, N. & Warrington, C. (2022) ‘Nothing about me without me’, in Holmes D (ed.) Safeguarding Young People: Risk, Rights, Resilience and Relationships, Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

HMIP (2023) Relationship-based practice framework. HMIP website

Hollenstein, T. (2015). This Time, It’s Real: Affective Flexibility, Time Scales, Feedback Loops, and the Regulation of Emotion. Emotion Review. 7. 10.1177/1754073915590621.

Holmes, D (Ed.) (2022) Safeguarding Young People: Risk, Rights, Resilience and Relationships. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Jerome, L., & Starkey, H. (2022). Developing children’s agency within a children’s rights education framework: 10 propositions. Education 3-13, 50(4), 439–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2022.2052233

Khoury, E., Boisvert-Viens, J. & Goyette, M. Working with Youth During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Adaptations and Insights from Youth Workers. Child Adolesc Soc Work J (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-023-00917-0

Koutsounia, A (2024) ‘Elieen Munro on the legacy of her child protection review’ Commuity Care

Lamph, G., Nowland, R., Boland, P. et al. Relational practice in health, education, criminal justice, and social care: a scoping review. Syst Rev 12, 194 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-023-02344-9

Lefevre, M. Hickle, K. Luckock, B (2019) ‘Both/And’ Not ‘Either/Or’: Reconciling Rights to Protection and Participation in Working with Child Sexual Exploitation, The British Journal of Social Work, Volume 49, Issue 7, October 2019, Pages 1837–1855, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcy106

Lefevre, M., Huegler, N., Lloyd, J., Owens, R., Damman, J., Ruch, G., & Firmin, C. (2024). Innovation in Social Care: New Approaches for Young People affected by Extra-Familial Risks and Harms (Version 1).University of Sussex.

Lewing, B. Beervers, T. Acquah, D. (2018) ‘Building trusted relationships for vulnerable children and young people with public services’ Early Intervention Foundation

Lloyd, J. Hickle, K. Owens, R. Peace, D. (2023) ‘Relationship-based practice and contextual safeguarding: Approaches to working with young people experiencing extra-familial risk and harm’ Children & Society. 2023; 00:1–17. |

Local Government Association (2024) ‘The Standards for Employers of Social Workers in in England 2020: Standard 3: Safe workloads and case allocation’ Accessed 7 July 2024: https://www.local.gov.uk/our-support/workforce-and-hr-support/social-workers/standards-employers-social-workers-england-2

Long, S. Ed. (2016) Transforming Experience in Organisations: A Framework for Organisational Consultancy. Routledge

Mann, D (2020) Gestalt Therapy: 100 Key Points & Techniques. Second Ed. London: Routledge

Maynard, L & Stuart, K (2018) Promoting Young People’s Wellbeing through Empowerment and Agency: A Critical Framework for Practice London: Routledge.

Millar, H., Walker, J. & Whittington, E. (2023) ‘If you want to help us, you need to hear us’ In Firmin, C. and Lloyd, J. (eds) Contextual Safeguarding: The Next Chapter Bristol: BUP.

Ofsted (2024) ‘Guidance: Inspecting local authority children’s services’ Gov.uk

Owens, R., & Lloyd, J. (2023). From behaviour-based to ecological: Multi-agency partnership responses to extra-familial harm. Journal of Social Work, 23(4), 741–760. https://doi.org/10.1177/14680173231162553

Pryce, J. (2012). ‘Mentor attunement: An approach to successful school-based mentoring relationships’ Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 29(4), 285–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s.10560-012-0260-6

RCGP (2022) Fit for the Future: Relationship-based care RCGP

Ruch G (2020) ‘Practicing relationship-based social work’ PSDP – Resources and Tools: Research in Practice.

Scott, S and Botcherby, S and Ludvigsen, A (2017) University of Bedfordshire Wigan and Rochdale Child Sexual Exploitation Innovation Project: evaluation report. March 2017. International Centre NatCen Social Research, corp creators.

Schön, D.A. (1992). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315237473

Stern, D. (1985). The interpersonal world of the infant. Basic Books.

Tackling Child Exploitation programme (2023) ‘Practice principles: be strength-based and relationship based’ Tackling Child Exploitation programme

Trevithick, P (2012) Social work skills and knowledge: a practice handbook. Third Edition. OUP.

Williams, J., Ruch, G., & Jennings, S. (2022). Creating the conditions for collective curiosity and containment: insights from developing and delivering reflective groups with social work supervisors (Version 1). University of Sussex. https://hdl.handle.net/10779/uos.23490086.v1

Winnicott, D.W. (1960). The theory of the parent-infant relationship. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis. 41, pp. 585-595.

Wroe, L & Pearce, J. (2022) ‘Young People Negotiating Intra- and Extra-Familial Hamr and Safety: Social and Holistic Approaches’ in Holmes, D Ed. (2022) Safeguarding Young People: Risk, Rights, Resilience and Relationships. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.